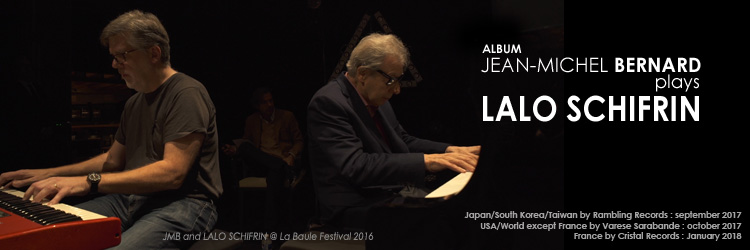

JMB PLAYS LALO SCHIFRIN

C'est l'histoire d'une rencontre entre deux artistes hors-norme. Mieux, d'un coup de foudre d'amitié. A priori, beaucoup de choses les séparent : la nationalité, la génération, le cadre et mode de vie… Mais, a fortiori, ce qui les réunit est encore plus vaste : le goût du jazz et de la musique moderne, le sens de l'humour, la dérision des êtres et des choses, le lien à Ray Charles… Paramètre essentiel, les oeuvres du premier ont façonné la vocation, sinon la culture, du second. Par ordre d'entrée en scène, ils s'appellent respectivement Lalo Schifrin et Jean-Michel Bernard. L'un a vu le jour en 1932 à Buenos Aires, berceau de Borges et Piazzola ; l'autre en 1961 à Montdidier, ville natale d'Antoine Parmentier, l'apôtre de la pomme de terre (d'emblée, ça fait moins exotique). Le récit de leur aventure partagée s'articule en trois actes, à la façon du théâtre classique.

Acte I, 1990

Pour la fin janvier, l'organisation du Midem charge le musicologue Alain Lacombe de coordonner un concert exceptionnel de Lalo Schifrin, à la tête de l'Orchestre National de Lyon, complété par une rythmique d'acier, Ray Brown à la contrebasse et Grady Tate à la batterie. Au programme, des oeuvres de Schifrin, bien sûr, mais aussi de Villa-Lobos, Francis Lai, Gillespie… et une suite française, autour de Ravel, Honegger, Delerue et Georges Auric. Pour arranger Moulin Rouge, Lacombe contacte spontanément un pianiste et compositeur de vingt-neuf ans, alors responsable musical de l'émission radiophonique L'Oreille en coin. « Je ne saurai jamais pourquoi il a pensé à moi, analyse rétrospectivement Jean-Michel Bernard. Car, à l'époque, je n'avais jamais écrit pour orchestre. En totale inconscience, j'ai accepté la proposition mais à peine le téléphone raccroché, je me suis dit : « Et maintenant, comment fait-on ? » C'était une impression étrange, celle d'être poussé tout habillé dans la piscine. » Intérieurement, Jean-Michel se revoit à dix ans vissé au téléviseur Radiola, rêvant face aux génériques de Mission: impossible ou Mannix, deux Everest d'efficacité et de sophistication mêlées. Cette commande, c'est surtout un prétexte pour rencontrer l'un de ses héros musicaux, Lalo Schifrin. Deux mois plus tard, comme dans un rêve éveillé, il assiste au concert où son premier arrangement symphonique est dirigé par le compositeur de Bullitt. Lequel lui dédicace le programme, en le félicitant pour la qualité de son travail. « J'étais tellement fier de le côtoyer pendant deux jours, se souvient Jean-Michel. Il avait (et il a toujours) la générosité et le magnétisme des monstres sacrés. Pour moi, c'était une parenthèse courte mais essentielle. Je ne pouvais pas imaginer qu'elle aurait une extension tardive, comme une bombe à retardement. »

Acte II, 2016

Un quart de siècle s'est écoulé. Dans l'intervalle, l'aura du grand Lalo n'a cessé de croître, d'électriser les nouvelles générations. Il s'est lancé dans une série d'albums et de concerts baptisée Jazz meets the symphony, déclaration d'amour à la musique au pluriel. Plusieurs cinéastes l'ont invité à revisiter son propre passé : Carlos Saura l'a ramené à ses racines argentines dans Tango, Brett Ratner l'a sollicité de manière référentielle pour la série des Rush hour, comme un lien vivant avec Bruce Lee. Pour beaucoup d'artistes contemporains, Lalo Schifrin incarne une sorte d'idéal : son sens mélodique, la luxuriance de ses orchestrations, son génie du rythme, son approche personnelle des folklores lui confèrent un statut singulier, celui d'un compositeur savant d'expression populaire. De son côté, le jeune Jean-Michel Bernard a tracé sa route et trouvé sa voie : ses indicatifs radio ont marqué l'identité sonore de France Inter, avant une fructueuse immersion dans la musique pour l'image, avec notamment Michel Gondry (La Science des rêves), Etienne Chatilliez, Francis Veber, Fanny Ardant ou Anne Giafferi. Pendant trois ans, de 2000 à 2003, il a été sur scène le dernier et indispensable accompagnateur de Ray Charles, le complice de son crépuscule. « Ce mec est un génie ! » s'exclamera le père de la soul, ahuri par la technique « feu d'artifices » du jeune Français. Au gré des projets, les circonstances amènent parfois Jean-Michel à lancer des clins d'oeil à Schifrin (le Rush hour « suédé » de Soyez sympas rembobinez de Gondry, l'influence bullitto-mannixienne qui sous-tend la partition de Cash). Mais depuis Cannes 1990, leurs chemins se sont plus jamais croisé. La musique de Schifrin, Jean-Michel vit avec elle au présent ; le souvenir de Lalo, lui, se conjugue au passé. Ce souvenir aura-t-il un avenir ?

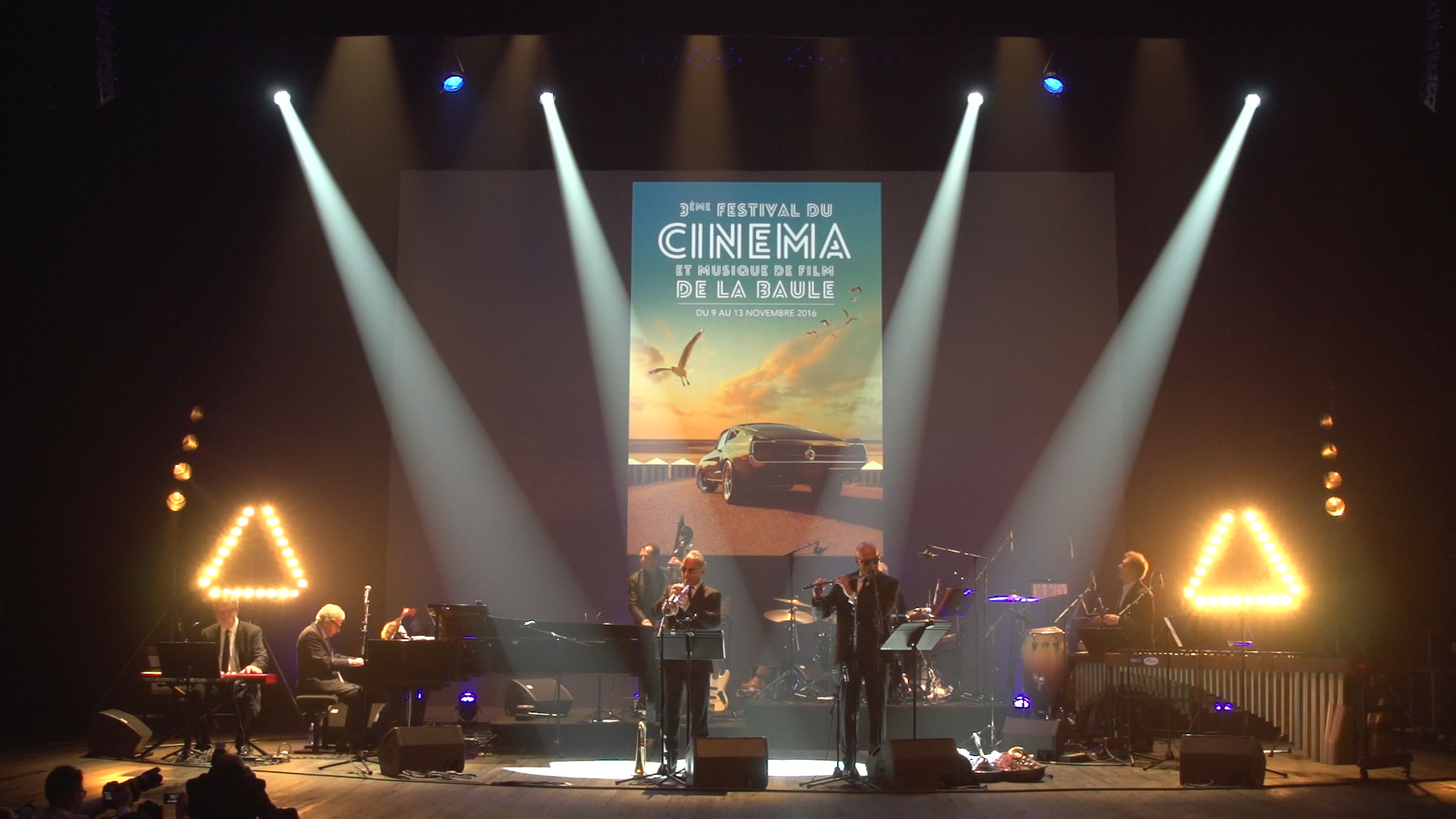

Au printemps 2016, une rumeur court, enfle et bientôt se confirme : Lalo Schifrin viendra en France en novembre, à l'invitation du Festival Musique et Cinéma de La Baule, piloté par Sam Bobino et le cinéaste Christophe Barratier. Il faut lui organiser un concert hommage. Consultant musical sur l'évènement, je souffle le nom de Jean-Michel Bernard. Je dirais même : je l'impose. Provoquer les retrouvailles entre Lalo et son émule tient de l'évidence, sinon de l'obligation morale. Comme ironiserait Michel Audiard à sa légion d'honneur : « Ce n'est pas un honneur que l'on me fait, c'est une injustice que l'on répare ! » Informé du projet, il faut à Jean-Michel un quart de seconde pour embrayer aussi sec. Cette fois-ci, il n'y a pas l'ombre d'un «Et maintenant, comment fait-on ? » A la façon d'un directeur de casting, il construit aussitôt un combo abrasif, autour du contrebassiste Pierre Boussaguet, disciple albigeois de Ray Brown, du batteur François Laizeau, du trompettiste Eric Giausserand, du saxophoniste québécois Charles Papasoff, du percussionniste Daniel Ciampolini. Et lui-même évidemment, oscillant du Steinway à un clavier Nord Electro 5. La nomenclature arrêtée, il se plonge avec volupté dans la confection des arrangements, sur une ligne de funambule : du respect mais de l'originalité, un souci de lisibilité persillé de chausse-trappes harmoniques et rythmiques. Tous les standards schifriniens passent à la moulinette Bernard : Mannix, Luke la main froide, Le Kid de Cincinnati, Bullitt, Dirty Harry… avec quelques pas de côté comme Tango, Les Félins ou Lalo's bossa nova. Sans oublier That night, la version vocale de The Fox, que Jean-Michel abandonne à son épouse Kimiko, artiste-potière à la ville, chanteuse au timbre de femme-enfant, fragile et aérien, comme hérité de Blossom Dearie. La veille du concert, le 11 novembre, Jean-Michel et Lalo se retrouvent au bar de l'hôtel L'Hermitage, à La Baule. La mémoire de Schifrin a effacé l'image du jeune arrangeur croisé à Cannes, vingt-six ans plus tôt. Mais dès que Jean-Michel se met au clavier, c'est l'électrochoc : assis sur un accoudoir, Lalo tombe à la renverse dans son fauteuil, littéralement soufflé. « Mais ce n'est pas un bon pianiste, assène-t-il, c'est un grand pianiste ! » Le lendemain, depuis l'avant-scène, Lalo devient spectateur de sa propre musique, découvre en direct l'éclairage d'un autre artiste sur son écriture. Assis à ses côtés, je le vois s'enflammer devant la cadence de piano qui conclut Luke la main froide (« C'est comme si Bill Evans était toujours vivant !) ou les chorus d'Eric Giausserand (« J'ai l'impression d'entendre Roger Guérin, le seul trompettiste français que Dizzy vénérait ! ») A chaque trouvaille, il me pince le bras : j'en ressortirai avec quelques bleus. A l'issue du concert, il doit rejoindre les musiciens pour un bis collégial de cinq minutes. Non sans un léger trac : voilà trois ans qu'il ne s'est pas produit en public. Après un Dirty Harry blues en duo avec Pierre Boussaguet, il se lance avec Jean-Michel dans un duel pianistique délirant sur Joyeux anniversaire (celui de Boussaguet, en l'occurence) avant de conclure sur une reprise incandescente de Mission: impossible… trente-cinq minutes plus tard ! Conscient d'avoir assisté à un happening historique, le public leur fait une standing ovation qui arrête le temps. Cette soirée, c'est objectivement une frontière intime, une césure. Avant le concert, il y avait entre Lalo et Jean-Michel un rapport de maître à élève ; à son issue, ils sont devenus frères. Le surlendemain, au petit matin, avant de prendre son vol retour pour Los Angeles, Lalo me glissera : « Ce tourbillon m'a fait un bien fou : j'ai l'impression d'avoir rajeuni de vingt ans ! »

Acte III, 2017

Le départ de Lalo et de son épouse Donna laissera à tous un léger vague à l'âme, un spleen post-schifrinien. Une douce mélancolie de voir l'évènement tant attendu déjà appartenir au passé. Chez Jean-Michel Bernard, il s'opère une sorte de transfert : sentimentalement, la place laissée vacante par Ray Charles est à nouveau occupée, enfin. Alors, pour que l'aventure continue, il décide d'autorité d'enregistrer le programme du concert en studio, afin de le publier en disque. Pour que ce moment de grâce ne soit pas qu'un souvenir chez les spectateurs présents à La Baule, le 12 novembre. Fin janvier, avec l'aide précieuse d'Eric Debègue, il convoque ses « Fab Five » pour trois jours de studio chez Cristal, à Rochefort, la ville des Demoiselles et de Pierre Loti. Galvanisés par l'acquis du concert, ils replongent avec délice dans le répertoire de Lalo, complété par une reprise de Manteca, le standard de Dizzy Gillespie. Ces séances, Jean-Michel va s'en servir comme d'une base sur laquelle, pour citer Boileau, il lui faudra « cent fois sur le métier remettre son ouvrage ». Rentré chez lui, saisi d'une frénésie perfectionniste, il réenregistre dans son propre studio certains claviers, écrit de nouvelles transitions à la suite de Dirty Harry, invite Philippe Chayeb à faire groover Bullitt de sa basse électrique, élabore un second arrangement du Tango del aterdecer, cette fois comme un dialogue entre le Stradivarius de Laurent Korcia et le violoncelle de Jean-Philippe Audin, fait surgir Kyle Eastwood en invité surprise de Dirty Harry… Tel un forcené de l'excellence, il recommence, défait, reprend, corrige, désosse, convie soudainement un corniste, remixe… C'est un processus sans fin qui bordure l'idée fixe, une quête d'absolu qui tutoie l'obsession. Au bout de plusieurs semaines, il faut le ceinturer. D'autant que, de l'autre côté de l'Atlantique, Lalo attend. Il a donné son accord immédiat pour prendre part à l'album. A une seule condition : venir l'enregistrer sur place, en Californie. Dans cette perspective, Jean-Michel lui réserve deux morceaux à deux pianos : Chano (originellement écrit pour Gillespie) et une longue introduction à The Plot, comme une joute fantaisiste nourrie de citations jubilatoires. Il échafaude aussi une suite originale combinant Recuerdos de Che! (sur un rythme de baguala) et le thème d'amour des Quatre mousquetaires, d'esthétique Renaissance, suite sur mesure pour Sara Andon, renversante flûtiste classique du nouveau monde. Comme il n'existe pas de demi-mesure à Bernard-land, l'intéressé loue le mythique studio A du Capitol Building d'Hollywood, hanté par les fantômes de Sinatra ou Nat King Cole. Un studio pouvant accueillir un orchestre symphonique juste pour… deux pianos de concert et une flûte. A l'échelle du projet, ce n'est finalement qu'un détail.

Le 2 avril, veille de la séance, rendez-vous chez Lalo pour lui faire écouter le matériel déjà enregistré et mixé. Il s'attendait à une stricte mise en boîte du concert, il prend de plein fouet des arrangements renouvelés, ciselés, affinés par la prise de son, le re-recording, l'apport de solistes inattendus. « A La Baule, c'était un magnifique enfant. Désormais, c'est un adulte » s'émerveille Lalo dans son langage imagé, l'oeil facétieux. Le lendemain, les trois heures à Capitol représentent le climax de l'album, son apothéose : une étape magique où le légendaire compositeur entre dans le regard de Jean-Michel sur sa propre musique. Leur ping-pong improvisé sur Chano s'aventure en terre inconnue, chacun cherchant à prendre l'autre par surprise, à mieux le provoquer. C'est aussi Lalo qui s'assoit derrière la console, aux côtés de l'ingénieur du son Gustavo Borner, pour prendre les commandes de la séance, avec une autorité bienveillante. Tel Don Siegel dirigeant Clint Eastwood, il s'adresse à Jean-Michel du micro-cabine : « Attention, dans la middle-part de Che!, essaie de jouer moins rumba ! » Ou alors, pour le thème d'amour des Mousquetaires : « A la dernière reprise, fais plutôt des triolets, ça créera un effet de surprise ! » A trois minutes de la fin de la séance, Jean-Michel se lance dans une relecture inédite de Mannix, sur un tempo de ballade et un rythme à quatre temps. Une émotion indicible fige le studio. Le morceau dure deux minutes quarante sept, les applaudissements spontanés de la cabine treize secondes : il est pile dix-sept heures. De façon non préméditée, l'album vient de trouver son architecture : avec une symétrie parfaite, il s'ouvrira sur une version vitaminée de Mannix et se refermera avec celle pour piano seul, plus intérieure, quasi-crépusculaire. Le temps d'immortaliser cet après-midi hors du temps avec quelques photos… et Lalo nous invite à célébrer l'amitié chez Gardel's, sur Melrose Avenue, le meilleur restaurant argentin de Los Angeles.

Vous l'aurez compris, le disque que vous tenez entre les mains tient de l'accomplissement, musical et humain. Jean-Michel Bernard y fait crépiter d'une nouvelle énergie la personnalité du génie argentin, tant son versant rythmique que lyrique. Une vingtaine d'oeuvres de périodes différentes, de langages différents, écrites pour des formations différentes sont homogénéisées par sa subjectivité. C'est autant un travail d'interprétation que de réinterprétation. Il en ressort aujourd'hui une fraternité inconditionnelle. Ses racines remontent à Cannes 1990 et, sans doute plus loin encore, aux samedis de pluie du petit garçon de Montdidier, qui attendait impatiemment le début de Mission: impossible. Lalo et Jean-Michel pourraient paraphraser l'aphorisme d'Auguste Renoir, d'une même voix : « Cet album nous a pris deux mois… mais nous avons mis cinquante ans pour y arriver. »

Stéphane Lerouge

This is the story of a meeting between two unconventional artists. No, better than that: friendship at first sight. On paper they have little in common, whether in nationality, generation, background or way of life… But because of their differences, what they actually share is all the greater: a taste for jazz and modern music; a sense of humor; the irony of things and people; Ray Charles… One essential parameter is the fact that the works of the one shaped the vocation, if not the culture, of the second. By order of appearance, they are, respectively, Lalo Schifrin and Jean-Michel Bernard. The first was born in 1932 in Buenos Aires, the cradle of Borges and Piazzolla; and the second in 1961 in Picardy, in Montdidier, to be precise, the birthplace of French potato champion Antoine Parmentier (a less exotic aura, admittedly). In accordance with the customs of classical theater, the tale of their mutual adventure unfolds in three Acts.

Act I — 1990

For the end of January that year, the organizers of MIDEM put musicologist Alain Lacombe in charge of coordinating a one-off concert with Lalo Schifrin conducting the National Orchestra of Lyon, an ensemble complete with an ironclad rhythm section in the shape of bassist Ray Brown and drummer Grady Tate. On the programme: works by Schifrin of course, but also pieces by Villa-Lobos, Francis Lai, Gillespie… and a suite française involving Ravel, Honegger, Delerue and Georges Auric. To arrange Moulin Rouge, Alain Lacombe spontaneously contacted a pianist and composer of twenty-nine, and then responsible for the music of the French radio show L'Oreille en coin. "I'll never know why he thought of me," says Jean-Michel Bernard in retrospect. "At the time, I'd never written for an orchestra. It was totally thoughtless of me to accept his proposal, but I'd hardly put down the phone when I was already wondering, 'So now what do I do?' It was a very strange feeling, the same as when someone throws you into the pool with your clothes on." Inwardly, Jean-Michel could see himself aged ten, glued to the Radiola TV in a dream brought on by the opening credits of Mission: Impossible or Mannix, twin musical peaks that combine the efficient with the sophisticated. This new commission was above all a pretext to meet one of his musical heroes, Lalo Schifrin. Two months later, as if in a waking dream, he was at the concert in which the composer of Bullitt conducted Jean-Michel's first symphonic arrangement. Lalo gave him an autograph (on his copy of the programme), complimenting him on the quality of his work. "I was so very proud in his company for two days," remembers Jean-Michel. "He had (and still has) all the generosity and magnetism of the legends we revere. To me, this was a short but essential parenthesis. There was no way I could have imagined that it would have a belated sequel… like a time bomb."

Act II — 2016

A quarter-century went by. In the interval, the overtones surrounding the great Lalo's name constantly grew, electrifying each new generation. Schifrin launched himself into a series of albums and concerts named Jazz Meets the Symphony, declaring his love of music in the plural. Several filmmakers invited him to revisit his own past: Carlos Saura brought him back to his Argentinean roots in Tango, and Brett Ratner solicited him referentially for the Rush Hour series like a living link with Bruce Lee. For many contemporary artists, Lalo Schifrin incarnates a sort of ideal: his feeling for melody and his lush orchestrations, his rhythmical genius and personal approach to folk music earned him a particular status, that of a learned composer whose expression was popular. For his part, the young Jean-Michel Bernard mapped his own path in finding his way: his radio jingles left their mark on the identity of France Inter's sound, and then came his fruitful immersion in film music, notably with Michel Gondry (Human Nature, The Science of Sleep, Be Kind Rewind..), Etienne Chatiliez, Francis Veber, Fanny Ardant or Anne Giafferi. Over the three-year period from 2000 to 2003, he was the ultimate and indispensable accompanist onstage for Ray Charles, whose twilight he accompanied. "This guy's a genius!" exclaimed the father of soul, astounded by the "fireworks" technique of the young Frenchman. As different projects came and went, circumstance sometimes gave Jean-Michel the chance for a veiled reference to Schifrin (cf. the « sweded » Rush Hour in Gondry's Be Kind Rewind, and the "Bullitt/Mannix" influence that underlies his score for Cash). But since Cannes 1990, their paths hadn't crossed again. Schifrin's music was something Jean-Michel lived in the present, but his memory of Lalo belonged to the past. Would it have a future?

In the spring of 2016, a rumor went the rounds, gaining in size and soon obtaining confirmation: Lalo Schifrin would be going to France in November, invited by the "Musique et Cinéma" Festival held in La Baule, piloted by Sam Bobino and filmmaker Christophe Barratier. A tribute-concert was to be organized in Schifrin's honor. As music consultant for the event, I slipped the name Jean-Michel Bernard into a conversation. I'd even say I imposed him. Provoking a reunion between Lalo and his emulator was more than stating the obvious; it was a moral obligation. As the witty Michel Audiard said when he received France's Legion of Honor medal: "You're not doing me an honor, you're making up for all the wrong already done to me!" When Jean-Michel learned of this, it took him less than a second to change gears. This time there wasn't even a hint of, "So now what do I do?" Like a casting director, he at once put together an abrasive combo. Surrounding bassist Pierre Boussaguet, a disciple of Ray Brown, were drummer François Laizeau, trumpeter Eric Giausserand, saxophonist Charles Papasoff from Quebec, and percussionist Daniel Ciampolini. Plus himself, obviously, oscillating between a Steinway and a Nord Electro 5 keyboard. Having settled the nomenclature, he dived voluptuously into the preparation of the arrangements, treading with the concern of a tightrope walker: respectful, but original, with a care for clarity that he sprinkled with traps in both rhythm and harmony. Every Schifrin standard went into the Bernard mixer: Mannix, Cool Hand Luke, The Cincinnati Kid, Bullitt, Dirty Harry… together with sidesteps like Tango, Les Félins (Joy House) or Lalo's bossa nova. Nor did he forget That Night, the vocal version of The Fox, which Jean-Michel surrendered to his spouse Kimiko—actually an artist-potter when not a singer—whose voice, half-child and half-woman, is fragile and ethereal, with a timbre like that of an heir to Blossom Dearie. On the eve of the concert, November 11, Jean-Michel and Lalo were reunited at the bar of the hotel L'Hermitage in La Baule. Schifrin's memory had erased the image of the young arranger with whom he'd spent a moment in Cannes some twenty-six years earlier, but as soon as Jean-Michel sat down at the keyboard… Schifrin looked as if he'd been electrocuted. Sitting on the edge of his seat, Lalo promptly fell backwards into it, his breath literally taken away. "But, he's not a good pianist," he cried, "He's a great pianist!" The following day, from the front of the stage, Lalo became a spectator of his own music, discovering in real time the light that another artist could throw on his own composing. Seated next to him, I saw him exult at the piano cadenza that brought Cool Hand Luke to its conclusion ("It's as if Bill Evans was still alive!") or the choruses of Eric Giausserand ("He makes me feel I can hear Roger Guérin; he was the only French trumpeter that Dizzy worshipped!") Each new finding made him grab my arm, and I escaped with only a few bruises. When the concert was over, he had to join the musicians for a collective five-minute encore. But not without a little bit of stage fright: Lalo hadn't played in public for three years. After a Dirty Harry Blues duo with Pierre Boussaguet, he launched into a wild piano duel with Jean-Michel on Happy Birthday—it really was Boussaguet's birthday—before ending on an white-hot reprise of Mission: impossible… thirty-five minutes later! The audience, fully aware that they had witnessed a historic happening, gave them a standing ovation that stopped the clock. As evenings go, this one was quite objectively a landmark, an intimate hiatus. Before the concert, between Lalo and Jean-Michel there existed a master-pupil relationship; afterwards, they were brothers. Two days later, in the early hours of the morning before he flew back to Los Angeles, Lalo whispered to me, "That whirlwind did me so much good… I feel younger by twenty years!"

Act III, 2017

The departure of Lalo and his wife Donna left us all with a slightly melancholy feeling, a sort of post-Schifrin spleen. There was a sweetly sad nostalgia in the realization that such a long-awaited event was already part of the past. Inside Jean-Michel Bernard, a sort of transfer occurred: sentimentally, the place left vacant by Ray Charles now had a new occupant, finally. So, for the adventure to continue, he decided to record the concert's programme in the studio, so that it could be released as a record. It had been a moment of grace, and it should now be something more than simply a souvenir for those who were there, in La Baule, on that November 12. At the end of January, with precious help from Eric Debègue, he summoned his personal "Fab Five" to spend three days at Cristal studios in Rochefort, the city of Demy's Demoiselles and Pierre Loti. Spurred into action by the concert's acceptance, they took another delicious dive into Lalo's repertoire, complete with a new reading of Manteca, the Dizzy Gillespie standard. Jean-Michel would use the sessions as a foundation on which, to quote Boileau, he would be obliged to: "One hundredfold upon the loom his work of art revive." When he went home, he was in the grip of a perfectionist's frenzy: in his own studio he rerecorded some of the keyboards, wrote new transitions for Dirty Harry Suite, invited Philippe Chayeb to add a groove to Bullitt with his electric bass, worked on a second arrangement of Tango del Aterdecer, this time making it a dialogue between the Stradivarius of Laurent Korcia and the cello of Jean-Philippe Audin, and then he had Kyle Eastwood spring from nowhere as a surprise guest on Dirty Harry… Like some maniac deranged by excellence, Jean-Michel started over, unstitched, refolded, corrected, boned and filleted, before suddenly bringing in a horn and mixing again… It was an endless process that framed an idée fixe, a quest for the absolute that bordered on obsession. After several weeks of this he was ready for a straitjacket. All the more since, on the other side of the Atlantic, Lalo was waiting. He had immediately agreed to be part of the album. On one condition: he wanted to come and record it right there in California. With that in mind, Jean-Michel reserved two pieces for him, each for two pianos: Chano (originally written for Gillespie), and a lengthy introduction to The Plot, like some fantasy joust nourished on jubilant quotes. He also built up an original suite combining Recuerdos from Che! (with a baguala rhythm) and the love theme from The Four Musketeers in Renaissance style, forming a made-to-measure piece for Sara Andon, a stunning New World classical flautist. In Bernard's world there are no half-measures, and so Jean-Michel rented the Capitol Building's legendary Studio "A" in Hollywood, a room haunted by the ghosts of Sinatra and Nat King Cole. Its capacity can accommodate a symphony orchestra, and now it was being used for… two concert pianos and a flute. On the scale of this project, the size was just a minor detail.

April 2 was the eve of the session, and a meeting was set up at Lalo's home so that he could listen to the material already recorded and mixed. He was expecting a strict take of the concert, but what he heard knocked him flat: renewed arrangements, finely chiseled and refined by the sound-take, the rerecording, the contributions of unexpected soloists... "In La Baule, it was a magnificent child. From now on, it's an adult," enthused Lalo in his colorful language, a facetious look in his eye. The next day, those three hours at the Capitol Building would represent the album's climax, its apotheosis: a magical phase in which the legendary composer would enter his own music through the eyes of Jean-Michel. The improvised table tennis session in Chano ventured into unknown territory: each musician was looking to take the other by surprise, the better to spur him on. Lalo would also take a seat at the mixing desk alongside sound engineer Gustavo Borner, and control the session with benevolent authority. Over the microphone in the sound cabin he spoke to Jean-Michel like Don Siegel directing Clint Eastwood: "More care in the middle part of Che! Try that with less rumba!" Or when they were playing the Musketeers love theme: "On that last repeat, triplets would be better—they'll come as a surprise…" Three minutes before the end of the session, Jean-Michel attacked a brand-new reading of Mannix, taking it at a ballad tempo in four. The studio fell silent, struck dumb by the emotion in the air. The piece timed out at two minutes forty-seven; the spontaneous applause in the cabin lasted thirteen seconds. The clock showed exactly five p.m. In a way that was totally unpremeditated, the album had just found its architecture: with perfect symmetry, it would open on a version of Mannix filled with vitamins, and close with the same piece played on the piano alone, introspective and almost crepuscular. There was an impromptu gathering for a few photos—a way of making a timeless moment immortal—and then, at Lalo's invitation, everyone trooped off to celebrate the warmest kind of friendship with the best Argentinean cuisine, at Gardel's on Melrose Avenue.

You'll have guessed by now that the record you're holding is something of an accomplishment, both musical and human. Here, Jean-Michel Bernard has captured the personality of this Argentinean genius and made it crackle with a newfound energy, in its rhythms as well as in its lyricism. Some twenty pieces of music from different periods, in different languages—and initially written for different musical ensembles—have been made homogeneous through subjectivity. This is as much a work of performance as it is a matter of reinterpretation. Its outcome, today, is unconditional friendship, one with roots that go back to Cannes in 1990 and, no doubt, even earlier, back to those rainy Saturdays when a little boy in Montdidier used to wait impatiently for the start of Mission: impossible. Lalo and Jean-Michel could paraphrase Auguste Renoir's maxim in unison: "This album took us two months… but we spent fifty years getting there."

Stéphane Lerouge / Translation: Martin Davies